Welwyn

The village of Welwyn in Hertfordshire has roughly the same population as Champagne-sur-Oise, between 4,000 and 5,000, but the boundaries of the Civil Parish of Welwyn also take in the communities of Oaklands, Mardley Heath and Digswell which are separated from Welwyn itself by fields and woodland. Consequently, the population of the Parish, at approximately 9,000, is twice that of the commune of Champagne. In addition, until the 1990’s, the adjacent Parish of Woolmer Green was part of Welwyn.

Welwyn, together with Welwyn Garden City and Hatfield, forms the Borough of Welwyn Hatfield which has its own council and mayor.

The focal point of Welwyn village is the church which is situated at the junction of High Street and Church Street. This central area of the village contains a number of historic and architecturally important buildings, such as Old Church House which dates back to the 15th century. This area is also the shopping district. Welwyn has many Inns and Public Houses; historically, it was a major coaching stop on the Great North Road. In recent years many of these buildings have become pub-restaurants.

The River Mimram which runs through the village is a mere stream compared with the Oise, but, with its ducks, is a much loved feature of the village. The stretch of river that runs alongside Codicote Road is bordered on the other side by the open area known as Singler’s Marsh which is a local nature reserve. At the opposite end of the village, in Prospect Place, is Welwyn Civic Centre, where many Twinning events are held.

Digswell

When the railway was planned in the mid-19th century, there was opposition from local landowners to the line passing along the Mimram valley so it was rerouted by means of a viaduct and tunnels through Digswell. The viaduct is an impressive edifice containing no less than 14 million bricks. Welwyn North station was built and this resulted in the development of Digswell. However, it remains a pleasant wooded area with a low density of housing. There is much commuter traffic to London via Welwyn North.

Oaklands and Mardley Heath

Development of this area did not start until the 1920’s. Bungalows were built as second homes to allow people to spend their weekends in the country. These have gradually been replaced by desirable detached residences. Mardley Heath itself was used for gravel extraction but has now been restored and is a local nature reserve supported by the volunteers of the Friends of Mardley Heath.

An Incredibly Short History of Welwyn

by Tony Rook

This article appeared, in translation, in the 25th Anniversary Twinning Weekend programme (1998)

It is difficult for us to understand the way of life of people in the past. From the time of the first farmers nearly 4,000 years ago until the coming of the railways 150 years ago, the countryside around Welwyn was entirely agricultural. With the exception of water-mills and windmills, all the work was done by the muscles of animals or men – and all the energy came from the plants which were grown to feed men and animals. People who work on the land don’t live in large towns, but in small scattered farms or in hamlets. Twice Welwyn has been exceptional, because of its location on two different roads there have been two different towns there.

The Roman Town

In the first century BC Iron Age people (Celts) settled close to a ford, where a track beside today’s School Lane crossed another which followed the valley of the River Mimram. There farms have been found at Linces, New Danesbury and Lockleys, and rich burials at Prospect Place. A century later the Romans widened and straightened the School Lane route, which became the main east-west road, joining the Roman predecessors of St Albans and Colchester. A small town grew on the west bank of the river in the grounds of the Manor House to serve as posting station and a market. It spread along the road as far as Hawbush Rise. Welwyn Roman Baths are part of one of the country houses (villas) and farms which flourished around it. The Romans no longer ruled the country after the 5th century.

The Saxons and the French

For more than a thousand years after the Roman period there was no town at Welwyn. We think that Christian worship continued because some 7th century Christian Saxons were found in its cemetery. They have been re-interred under the church. Later, in the will of a Saxon lady we read of a monasterium (group of priests serving an area) at Welwyn (Welingum) in the 10th century, and a priest was Lord of the Manor (of Wilga) under the rule of the Norman French in the 11th. If there was a village it must have been small and unimportant and for centuries most of the local track ways by-passed it.

Coaching Days

The settlement had new life breathed into it at the middle of the 17th century, when well-to-do travellers wishing to go north from London found that the Old North Road – on the line of the Roman Ermine Street, about 12km east of Welwyn – was crowded with, and churned up by, goods traffic – carts and pack horses – bringing produce from Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire and North Hertfordshire to London. Seeking an alternative route, they found there was a good road to Hatfield, and the remains of part of the old Roman road north from Welwyn. By taking a poor, muddy and perilous route through lanes, they joined the two roads, producing a north-south route, the Great North Road. Welwyn became once again a posting station on a main road and a town grew, this time on the east bank of the Mimram.

For two hundred years the town flourished, and several inns and public houses were provided for travellers and local trade. In the late 18th century several towns in England became spas, where rich people came to drink or to bathe in local spring waters, which were believed to have medicinal properties, and the Rector of Welwyn tried – and failed – to make the town such an attraction. His Assembly Rooms, for public meetings, which even contained a theatre, are now cottages in Mill Lane. In the 19th century the Great North Road was improved and Welwyn became the centre of mid-Hertfordshire. One inn, The White Hart, it is said, provided horses for more than eighty coaches every day! There were many rural industries there, including brewing and making shoes and beehives. There was a main post office and a police station, even a gasworks.

The Railway Age

The Great Northern Railway was built in the middle of the 19th century but, because so many rich landowners had created ornamental parks along the river, the engineers, many of whom were French speaking, having spent time in France constructing the chemin de fer, were forced to take it not along the valley but across it about 2km to the east of Welwyn, on a great viaduct and through tunnels. When the railway opened, the traffic passed Welwyn by. Although the coaching trade which had caused its prosperity died, however, the town survived as an important commercial, industrial and administrative centre.

Motor Transport

At the beginning of the 20th century, road transport began to make comeback, and the internal combustion engine brought more and more traffic. The motor car put Welwyn with an adventurous distance of the capital, and numerous road houses were built. Visitors who saw the local woodlands as being an attractive place to retire began the settlement of the Oaklands area. By the 1920’s a policeman was needed to control the traffic at the junction of Church Street and High Street and, in 1927 one of the first by-pass roads was opened to allow travellers to avoid the town.

New Towns

At this time an unforeseen threat appeared to the commercial life of the village: Welwyn Garden City. On an almost-deserted area of agricultural land about 4km to the south-east (none of which, despite its name, was at that time in Welwyn) construction was begun of an entire new town. At first it was not easily accessible from Welwyn (which then started calling itself ‘The Village’) and the effects were slow, but, for example the main post office and the police station went to the new centre.

The Garden City was intended to provide its inhabitants with employment within walking distance of their homes, but commuting – that is, living in the country and travelling by train into London to work had already become well established. It was not until after the 1939-45 war that the government saw that the idea of providing both employment and housing in the same place was a good idea and started to create New Towns – which included, locally, Hatfield, Stevenage and a greatly enlarged Welwyn Garden City. These towns had large new shopping centres, which attracted people from outlying villages and new roads made ‘The Garden City’ easily accessible from ‘The Village’.

The Motorway

From the mid 1950’s, motorways began to be built, with special rules intended to allow fast unimpeded national travel, and in 1972 the A1(M), beside the by-pass, took traffic completely past Welwyn so close that it could be seen – and heard – it could not turn off.

The almost universal ownership of private cars attracted people to travel to larger shopping centres, rather than to local shops. In recent years the increased mobility which resulted from motorways allowed the construction of large out-of-town shopping areas located close to main roads and with free car parking and visiting these has almost become a recreational activity. The smaller shops in villages and even in towns find it difficult to compete. When the Anglo-French Twinning took place, Welwyn had two grocery stores, two fish shops, two pharmacies, greengrocers, antique shops, cafés and restaurants. In recent years many retail shops have closed, to be replaced by offices – and estate agents!

Current Trends

Commuting both to London and to other towns to work is now seen as the normal way of life, but although ‘The Village’ – as a place where to live, work and shop – has lost its original meaning, living in a village has become such an attractive idea that the price of even a small cottage in Welwyn has risen astronomically. Today modern dwellings are being crowded into every open space – even into the gardens of larger historic houses, many of which are themselves demolished or sub-divided into smaller apartments.

Champagne-sur-Oise

Champagne-sur-Oise is a large village and commune of some 4,400 inhabitants in the department of Val-d’Oise within the Île-de-France region. It is some 40km (25 miles) north of Paris and stretches for 4km along the northern bank of the River Oise, a wide navigable river which flows into the Seine. There is a sailing club situated on the southern bank opposite the village. The village itself occupies the valley and part of the higher ground. The surrounding area is a mixture of agricultural land and woodland, with panoramic views over the valley from vantage points on the high ground.

The Mairie is located in the centre of the village, in Place Général de Gaulle. The mayor, Mme Corinne Vasseur, is a keen supporter of the twinning as is her predecessor, M Joël Berniot. Alongside the Mairie is the Centre de Secours, the fire and ambulance station. The Sapeurs-Pompiers (Fire Brigade) are also very involved in twinning events. They even provided the transport between the rail station and the Mairie for us on our visit in May 2009. With blue lights flashing and sirens sounding, the whole village knew we had arrived. Some welcome!

Also in Place Général de Gaulle are the historic church of Our Lady of the Assumption, the War Memorial and the École Maternelle Centre. There are several elegant town houses in the old part of the town as well as modern estates on the periphery. To the west of the village there is an imposing mansion called Montrognon, which was where school parties from Welwyn stayed in the 1970’s. The Rue de Welwyn leads to the Municipal Park and the CCS (Complexe Culturel et Sportif) where the main event of the twinning weekend is usually held. The other sporting venues, for football and tennis, are the Parc des Sports and Stadium, which are located at the northern end of Rue de l’Hôtel-Dieu.

Champagne was originally a rural agricultural village. Amongst other crops, grapes were grown but there has never been any connection with the sparkling wine of the same name that is produced in the region around Reims. Until recently, the largest local industry was the generation of electricity in the EDF power station at the eastern end of the village. This was affectionately known as the ‘Cathedral’, because the twin towers of the plant resembled the façade of a typical French cathedral. Alas, the plant has been closed and the towers demolished. There is some light industry remaining in the district and also many residents commute to Paris.

Despite its proximity to Paris, Champagne-sur-Oise has retained a lot of its character and charm.

History of Champagne-sur-Oise

Champagne-sur-Oise, like Welwyn, was a Roman settlement. Little is known of its early history except that it was called Campania Villa. This name crops up again in the 7th century when it is recorded that King Dagobert gave the land around Champagne to the Abbey of St Denis. There was a fortified castle, of which nothing remains, although the surrounding land is still called La Citadelle.

The land reverted to royal ownership in 1223 when it was purchased by King Philippe Auguste from the Comte de Beaumont. King Louis IX (St Louis) often stayed in Champagne. The church had been built in the 12th century but was extended around this time by the king’s architect, Pierre de Montreuil, who was also responsible for the construction of L’Abbaye de Royaumont and la Sainte Chapelle in Paris. Also in the 13th century a hospice (Hôtel Dieu) was created; this was held by Cistercian nuns. Part of the building still exists today.

Général Corbineau, one of Napoleon’s generals, lived in Champagne at the beginning of the 19th century in the Château de Montigny and the tombs of the general and his wife can be seen in the churchyard.

The village was the scene of some fighting during the Second World War. The church was hit by allied fire from the opposite bank of the Oise and the château was burnt down by the retreating Germans. Part of the grounds of the château was purchased from the Corbineau family to construct the municipal park. The park was officially opened on the same day in 1973 that the Twinning was formalised.

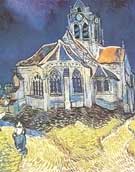

The Van Gogh Connection

It is probable that Vincent Van Gogh knew both villages.

His sister, Anne, was employed as a school mistress in Welwyn and lived at Rose Cottage¹ in Church Street. Vincent is recorded as having visited her there, famously having walked all the way from the Channel coast.

Later, when suffering deep depression, he took up residence in Auvers-sur-Oise, not far from Champagne. This enabled him to be close to his brother Theo and to be treated by the physician, Dr Gachet, who had been recommended to him by Pissarro. Sadly, his state of mind deteriorated and it was in fields near Auvers that he fatally shot himself. Both Vincent and Theo are buried in the churchyard there.

Our French hosts have taken us to Auvers-sur-Oise on more than one occasion, to Van Gogh’s lodgings, the Church and the Château (which is devoted to the history of Impressionist painting).

¹ Recent research by Tony Rook suggests that Anna Van Gogh lived and worked at Ivy Cottage on the corner of Forge Lane, rather than Rose Cottage.